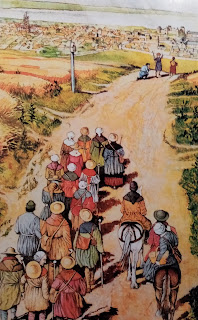

Pilgrims

Pilgrimage

With more than its share of patron saints, Scotland was a magnet for pilgrims from abroad. Scots also took to the holy routes, which were often long, arduous, and dangerous.

Pilgrimage and the cults of saints were as popular with the Pictish, Irish, Norse and Scots peoples of Scotland as with any others in Christendom. With major shrines at the heart of important reliquary churches at Iona, St Andrews, Kirkwall, Whithorn, Glasgow, Dunkeld, Dunfermline and Tain, Scotland had more than its fair share of patron saints, ranging from Andrew – an apostle of Christ - through national, indigenous saints such as Ninian, Columba and Kentigern, to a multiplicity of lesser holy men and martyrs.

From the earliest times, Scots were recognised on the pilgrimage of the early missionaries were elected saints, with some, such as Columba of lona, who died in 597, regarded as saints even during their own lifetime. These places of burial became renowned.

Possibly the oldest shrine of all was the tomb of St Ninian at Whithorn in Galloway. He is believed to have been the leader of Romanised Christians here in the 5th century, and recent excavations around his hilltop shrine have revealed intensive phases of the church building from then up to the Reformation.

Devotion to Ninian remained constant throughout a period of more than 1000 years, transcending numerous shifts in power within the region.

The other important early cult was that of Kentigern, also known as Mungo, who is believed to have died around 612, and whose burial place inspired the creation of Glasgow Cathedral. This is the most complete, large medieval reliquary church to survive in Scotland, enabling the modern visitor to easily replicate the experience of the medieval pilgrims.

What was the motivation for pilgrimage?

It was to attain the greatest prize of all-salvation of the immortal soul. The people were taught by the Church that they were destined for the fiery pit unless they took positive action to remove their sin. Pilgrimage can therefore be seen as a metaphor for the medieval life-a journey to achieve salvation, with pilgrimage acting as a bridge between this world and the next.

The shrines containing the bones of saints played a crucial role in the forgiveness of sin, in the expiation of a crime, even manslaughter, and in the witnessing of vows and contracts. The effectiveness of the pilgrimage was multiplied if the penitents were present during auspicious festivals such as Easter, or the feast days of the individual saints.

Not all would have lived up to the pious ideal, for some, pilgrimages represented a convivial excuse for travel and fun, which would otherwise have been impossible within a society where most were bound by rigid ties to land, family, and service. Preparation for pilgrimage might have been the only occasion when poor peasants were permitted to travel far distances from their parish.

Before travel, written permission had to be granted by the parish priest, and warm clothing obtained, forming the universally recognised pilgrim's garb. This consisted of a rough tunic and a with a broad-brimmed hat, a staff, water bottle, and a small satchel for food, known as a scrip.

Safe conducts were obtained from the English Crown for pilgrimages outwith Scotland, especially during the long centuries of conflict between the two countries from the later 13th century on. These safe-conducts could be for years, especially for pilgrimage to Rome or the Holy Land. There was a good likelihood that the individual might never return, having fallen prey to disease or cut-throats.

The property and estates of pilgrims especially lordly ones, were placed under the protection of the king, and no legal claims against the pilgrims could be settled until their safe return The night before departure, the pilgrim's staff and scrip were placed on the high altar to absorb the protection of the Holy Spirit.

Safe-conducts were also given in Scotland.

In 1427 James I issued a general safe conduct for the benefit of pilgrims from England and the Isle of Man coming to St Ninian's shrine at Whithorn, specifying in the condition of their are to come by sea or land and to return by the same route, to bear themselves as pilgrims are to come by and to remain in Scotland for no more than 15 days; they to wear openly (pilgrim's) badge as they come, and another on their return journey.

The pilgrim's journey was a complex of of ferries, roads, bridges, and fords. Chapels, hospitals, and inns were created and maintained to ease the way for them. The support of this infrastructure was a recognised act of piety.

Travel was slow, arduous and often dangerous, and it was believed that the harder the journey, the greater the benefit to the soul. This is illustrated by the encounter on the way to Whithorn in July 1504 between James IV and some "puir folk fae Tain pasand to Whithern".

James himself was a devout pilgrim, well acquainted with Tain in Easter Ross from his annual visits to the great shrine St Duthac. But for the people of Tain it was not sufficient to attend their own shrine. Instead they chose to journey hundreds of miles across the spine of Scotland to another famous shrine in Galloway.

Pilgrims' ferries were provided on two crossings of the Forth for bona fide pilgrims to the shrine of the apostle at St Andrews. They qualified for free passage by displaying the oppropriate demeanour, garb, and pilgrim's badge. The most famous was the western crossing, known to this day as Queensferry, endowed by St Margaret, wife of Malcolm Canmore in the 11th century .

Her biographer, writing shortly after her death in 1093, recorded that she not only provided ships for the crossing, but also established hostels on either side of the Forth with staff who were instructed to wait upon the pilgrims with great care. Aiding pilgrims like this was believed to earn the giver points for reception in Heaven.

Scots pilgrims' badges provide reliable evidence of the movement of people, of arduous journeys, while also underlining the tangible devotion to individual saints.

There is also a body of pilgrimage artefacts that illustrate Scots pilgrimages further afield, to shrines in England, Europe, and the Holy Land.

Pilgrimage helps us to understand the design and function of many of the great churches and cathedrals of medieval Scotland, not only their use in the often-exclusive worship of monks or clergy but also their role in popular religion.

Great reliquary churches were built to house the relics of the saints, thus making them accessible to the faithful, while keeping them secure.

Pilgrims to St Andrews in the 15th century would have been drawn towards the Cathedral by the distant view of tall spires and towers. Having passed through the burgh gates, they would have mingled with the crowds who came, not just for the religious services but also for the secular festivities and markets.

Their sense of anticipation would be heightened as they entered the sacred of the Cathedral through the north door and joined the shuffling throng following the well-worn route towards the great shrine. As they moved east around the high altar, their senses would be assailed by incense and golden candlelight, glistening on statues, wall-hangings, and tomb effigies.

The pilgrims then found themselves in the shrine chapel, in the presence of the relics of the first chosen Apostle of Christ, housed in a great jewelled box called a chasse, raised up for security and visibility. The psychological effect of this experience – the huge scale of the building, coupled with the spiritual impact and the crush of unwashed humanity-would have been overwhelming for many. So the stage was set for healing miracles.

Comments

Post a Comment